Collusions: Conversations with architecture

- iliso_ ekapa

- May 28, 2021

- 18 min read

GSA Unit 19 tutors Tuliza Sindi & Muhammad Dawjee

AS A REFLECTION ON THE FIRST YEAR OF ITS RUNNING IN 2020, Unit 19 of the Graduate School of Architecture (GSA) in Johannesburg outlines the conversations it has with the Architecture discipline, in efforts to make better sense of how it can – in collusion – be most significantly in service to the truths of the society it’s in.

While on an hour-long afternoon commute home, 19’s taxi moves through Maboneng1, which sparks questions that compel him to call Arch for what feels like the 1000th time in just this week.

He calls Arch.

Arch is in her New York, industrial chic-style Hallmark House apartment in Maboneng, overlooking the city, in full concentration at her drawing board. All of her days resemble one another. She can always be found at her drawing board with a cigarette in hand and Tracy Chapman playing in the background.

Arch is startled by her ringing phone. Letting out a disapproving sigh, she contemplates whether to pick up the call or not.

She does.

Arch: 19…eight calls in two weeks!? You’re like a teenage girl! At this rate, I’m convinced you have a crush on me. What have you seen this time that you feel is so important for me to know?

19: (smirking) Don’t you just wish Arch? Hello to you too.

Arch: (lets out an impatient sigh) You know I don’t do small talk. What is it?

19: So, I’m on the bus on my way home and I just went past your neighbourhood. It reminded me of something I wanted to discuss with you about it.

Arch: I’m not interested in what you –

19: It’s like a socio-political and economic choreography you keep having us perform; a show on constant replay. The show’s main plot line is ‘white flight’2; the wealthy – mostly white – flee from the poor – mostly black. Some of our most recent projects; projects as fresh as (sends Arch a WhatsApp image) Midrand’s Falcon skyscraper in Waterfall city is, like clockwork –

Arch: Really, you’re just going to dive into the heavy topics in the first minute of the call? Not even a warm-up? Goodbye 19. (mumbles) So inconsiderate!

Arch hangs up.

19 lets out a satisfied laugh while he continues to observe the city as he moves through it. He eventually gets off at his final stop, and begins his twenty-minute walk to the Rivonia3 cottage rental he calls home. Upon arrival, he quickly settles in to continue his work from home. At his worktable, he sees some notes he wanted to discuss with Arch. As he prepares to call her, he remembers that she never takes more than two of his calls in one day. So as not to forget, he decides to send her a voice note instead.

19’s voice note to Arch:

(enthusiastically) Hi again, it’s me, your fave, (cheekily) lol. I know how much you love my unsolicited critique and advice, so I thought I’d share some more with you.

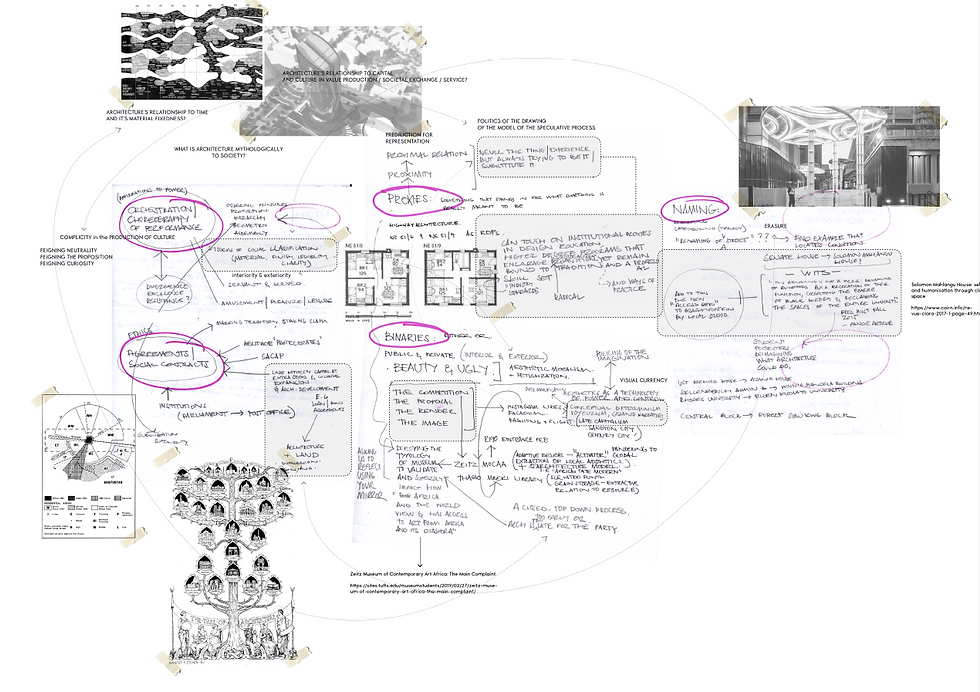

19 pins his notes to his notice board in front of him as he continues talking. He takes on a more serious tone.

19: I have some notes in front of me that I made but I also want to say what I intended to earlier, before I forget. When I was moving through Maboneng, it reminded me of how you reproduce forms of fleeing and privately policed segregation zones through most of your proposals for our ‘collective’ futures. Maboneng performs European urbanity as well as a reformed black middle class simultaneously, while making clear where the space of the wealthy begins and the space of the poor ends. Actually, what’s more obscene and perhaps audacious about Maboneng’s typology of segregation is that the proximity between poor and rich is so minimal; it’s a street apart, unlike during apartheid where they put significant distance between these conditions, like entire industrial neighbourhoods. That typology that no longer needs large scale buffers to enforce segregation is displaying a scary kind of mastery of its production on your part. It makes me think of one of the points I have in front of me, about how you produce proxies. Wait, uhm, give me a sec.

19 stands up, and accidentally sends the voice note as he reaches to unpin a part of his notes from the board. With the notes in his hand, he starts pacing up and down, and records a new voice note.

19 starts a new voice note to Arch: (apologetically) Uhm, my notes are all quite jumbled so you’ll have to excuse me for jumping between themes and for accidentally ending the previous voice note, but, as I was saying, Maboneng as a proxy masquerades as evidence of upward mobility for the historically disadvantaged, when what it’s really revealing is inequality along class lines. Come to think of it, you design proximities all the time, whether geographically, typologically, relationally or definitionally, then package the product as the same as what it is in proximity to. You’ve approached our housing crisis that way, where you’ve rebranded, repurposed and renamed the NE51/6s and NE51/9s4 into RDPs5, where it then serves as a proxy for dignified human and humane settlements. You’ve probably seen comparative images many times but I’ll still send some examples, because the differences are truly negligible. Anyway, that proxy affords you a quantifiable appearance of progress and resource compensation without actually transforming the system of racialized poverty and capital enslavement in any real way. It looks like your entire form of practice is purely cosmetic, where your aesthetic language is that of capital production, maintenance, and control. Actually, no wonder you rename so often. You first reframe something’s meaning and then build infrastructures that support and reinforce that new meaning, which choreographs our relationship to that new meaning and cements our agreements to it. These reframed objects,

and their infrastructures then anchor themselves as the foundational framework of meaning upon which all other proposed meanings are measured against.

19 pauses as he comes to a realization.

19: (drawing out his words) Oh, you’re so slick Arch! Your characteristics are always working together to reinforce one another. You’re a trap!! So that means –

While speaking, 19 looks at the time on his phone and notices that he has been recording for a while. He decides to end the voice note at that point.

19’s voice note to Arch in closing:

19: Damn, I’ve been recording for over 10 minutes, this has turned into a soliloquy. I’ll end it here for now. Let me know your thoughts on my points tomorrow. I’ll give you a call. Don’t let it ring too long; I’ll start thinking you’re playing hard to get (cockily), lol. Goodnight.

Arch wakes up to, among other things, a string of notifications from 19’s voice notes. She ignores them and goes about her day.

During his lunch break at work, 19 takes several flights of stairs back to the ground level and a steps out of his office onto the street. 19 checks in with Arch about the voice note he left the day before.

19 sends a message to Arch:

Arch does not respond.

After a few minutes, 19 proceeds to call her.

Arch, again at her drawing board, mutes 19’s call. As always, she contemplates whether to pick up or not.

After several rings, she does.

Arch: Why do I even…

19: (enthusiastically) Good morning Arch!

Arch: (slothful) Good afternoon 19. What do you want?

19: Have you listened to my voice note? It would make for a really good conversation. Don’t you always say you want to be provoked and be provocative? You’re always looking for relevancy are you not; your purpose for existing? I’ve sent some great points for you to consider on your evolutionary journey.

Arch: Who said I’m looking for relevancy? Do you know who I am? Do you know what I embody? I’m –

19: Yeah, yeah. You say that to all of us when we first meet you, but once we get to know you, it becomes clear that you’re in a constant state of suffering, and you pass that suffering onto us.

Arch: You talk like you know me, whilst you’re way too young to know or understand what I’ve been through.

19: But I don’t need to be old enough, ‘cause you tell me what you’ve been through all the time, and then you put us through it. We’re all suffering from not knowing what our value in society is anymore. Is it aesthetic, social, political, infrastructural, scientific? Are we meant to bring ideas of the future to the present before they have arrived, or are we meant to pursue issues after the fact to reactively resolve them? Would you say we’ve really come to terms with the harm we cause, some of which are the problems we’re always too late to claim, acknowledge or fix and too quick to enforce upon these conditions thin and poorly informed solutions?

Arch: 19, you’re not a therapist, so don’t psychoanalyze me and don’t project your issues onto me. Your guilt is not mine. It’s not my job to explain and quantify my value to anyone. I’m always misunderstood and mischaracterized and people like you constantly attacking me does nothing to relieve me of that. So, thinking that you’re helping me is absurd and arrogant.

19 senses Arch’s defensive stance and pauses to recalibrate.

19: (in a slower, more nurturing tone) I know I tease and prod at you a lot Arch, but I’m being quite serious. I feel like we have blood on our hands. I’m not just saying that figuratively, and I can’t say that without including myself.

Arch was going to match 19’s more toned down demeanour, but the final part of his statement aggravates her.

Arch: (agitatedly and impatiently) Not this again 19! You’re so naïve about the world sometimes. We can’t build worlds that are rosy and wonderful for everyone. Even as I’ve evolved, it’s a truth that’s never waned and one I’ve needed to come to terms with. What you’re guilty of is sustaining people’s hopes in those worlds being possible at all. You have to come to that realization quickly, so that you can get to a place of being as productive as you can be under the circumstances. You criticize so much of what I’ve done, but in reality, the fact that I even have things to criticize is what should really matter. It’s so easy for those like you who haven’t built as much as me to be without blame, because you have little to nothing to show for your convictions…and student work doesn’t count!

19: That’s a fair point Arch; I don’t have that much built for you to criticize – yet, but your devaluing of what I have built in thought and in research practice is an age-old tension you keep alive, and one that’s so binary in thinking; that building is valuable, while teaching, not so much. What’s unfortunate is that you think that way about everything; you even produce it. It doesn’t seem possible to you that complex conditions can simply coexist without posing a threat to one another, or without the one depending on the definition of the other to hold meaning. It polices the imagination and muddies nuance, rendering what’s either between or beyond those definitions invalid or suspicious.

Arch: That’s hard for me to accept as a flaw 19, because one of my inherent roles is to produce binaries: what is inside and what is outside, what remains dark and what is lit, what is above and what is below; the list is endless. To ask me to not produce binaries is like asking me to not breathe.

19: I understand your argument, but even in your response you’re demonstrating an inability to see nuance. To your examples, there are intermediary spaces like verandas that sit between being the inside and outside; conditions such as dimmed lighting that presents a unique experience from dark or lit; structures such as half-basements that sit both below and above ground simultaneously. Now I admit that those are simplistic and harmless examples, but the harm of that practice comes in when you apply that narrow thinking to how you socially, politically and economically organize.

Arch: Okay? Give me an example of how I do that.

19: Okay. I’ve been looking into malls as a condition of this. As a nation, we’ve barely come to terms with what a collective spatial condition of publicness could mean typologically, because our public lives were completely and violently separated, and have remained so. Under an apartheid framework, we were given different types of shared amenities and public organizational systems. Today, we find ourselves with two prominent conditions of publicness: fenced off or boundaried and privately policed spaces like our parks and malls, and commercial spaces like Starbucks and our transport depots. In fact, the only time we are all really able to cohabit the public realm with fewer class or race filters is through national events, like our sports matches or political rallies, and those are rare, fleeting and carnivalesque, while publicness remains omnipresent. So, through our hostile and politically prescriptive typologies, you produce new definitions of public and private, and those definitions – although skewed – are always relational to one another; and in that way validates itself. You’ve somehow made spaces with economic and geographic restrictions represent, in name, a concept of publicness that is profoundly contradictory. The blessing in what it does do, is that it tells the truth of how we co-exist; we form pockets of exclusion with nested definitions of public to private, or welcome to unwelcome. Come to think of it, that redefinition is one of the ways you rename. As I mentioned in the voice note, you also did that at –

Arch: Just hold on 19. Before you start to reference your elaborate voice note, give me ten minutes to go through it so I can get up to speed. I’ll call you back in a bit.

19: Oh sure, I’ll be here.

Arch hangs up and listens to 19’s voice note from the night before. Once done, she calls 19 back.

19: Hey, are we all caught up?

Arch: Yes; so you stopped at my practice of renaming, which might I add is also one of my inherent functions. How else would you distinguish between a place to sit and a place to sleep, a place to eat and a place to read? What are they if not meaningless without my designations of them?

19: Again, I agree. I guess I’m trying to show you how those characteristics can and are being corroded, and I’m arguing that perhaps it’s our responsibility to not simply keep exercising those traits even after they have been weaponized, but to reform them to their natural functions, when they were in service to our shared need for ordering, patterning and ritualizing outside of the need to objectify, extract and control. Before your listening break, I was going to give the very recent example of the WITS6 Gateway designs by Local Studio; I’ve just sent you an image.

They’ve ironically named it a public space and urban design intervention, yet it is an exclusive and controlled entrance that gives the illusion of open access and integration. In reality, it is a part of the institution’s language of restriction, with no visual access or active public edges. What is contained has no relationship to what is being kept out. They might argue that the light fixtures are an offering to the public, but in reality, it serves as an added surveillance measure for what’s within the campus. You’ll see also how they give the cost of the project in US dollars, which brings up questions about whether their audience is really the people they are designing for. It makes me question who – or perhaps what – they are in service to. To the idea of reclaiming your natural characteristics from their corroded states, the #FeesMustFall students offered up that provocation to you. I’m paraphrasing now, but they said of renaming buildings within their academic institutions, something to the effect of how renaming is not a mere renaming of buildings, but a recreation of their function, correcting the erasure of black history and reclaiming the spaces of the entire university. Unfortunately, there are many forces at play that can minimize its effectiveness, such as economic or geographic inaccessibility or unreformed course structures, but the point remains and is an important one to investigate.

It just becomes a realization for 19 how open to the conversation Arch is seeming. He is taken aback by this.

19: Before you engage anything I’ve just said, I’m realizing that you haven’t been reacting with your usual defensive and impatient stance. Where is the sense of openness to this conversation coming from?

Arch: Well, perhaps it comes from having had those same conversations with myself many times. In reality, I do understand and see value in what you’re saying, it’s just that some of the unjust conditions you’re outlining are the conditions I come from, yet I find myself trapped in a cycle of perpetuating it. That’s not an easy truth to acknowledge; you can understand that right? And if or when you ever get it right, perhaps you can share that just as passionately as you share my faults with me. I’m not very hopeful for myself but I can afford you hope.

19: It’s hard for me to not come across as simply judgmental, and to be honest, I might be projecting the judgement I place on myself. I sometimes find myself uninterested in investigating, documenting, theorizing and inhabiting my own forms of negation, because it requires me to remain within the dynamics of oppression, resistance and agency. I feel resistant toward co-signing those as the dominant frames through which the way I see the world should be thought through, theorized and practiced. Sometimes I’ve felt intellectually cornered by being sent to the Eurocentric archives of us, to discover our mis- and overrepresentation simply for the purpose of contesting it. That position of resistance and tension rather than invention, is placed along a binary spectrum that renders the pursuit of invention and human praxis – to borrow from Sylvia Wynter – negligent. So, with my words might come a bit of envy Arch, that you give yourself the permission to invent, which for me registers mostly as repetitions of what already is, but in new skin; pun intended. Historically, innovation for us was denied, destroyed or punished, and we could only ever react to more powerful forces. Perhaps your habit of reacting rather than truly innovating is one of my triggers, because true invention for you seems unintelligible. When will the appearance of moving forward stop being enough for you? When will you challenge the myth that you are?

Arch: What do you mean by that, 19?

19: You remain cleanly an expression of the Western ideology and culture that built you as a discipline. Let me fetch some of these diagrams. Two that immediately come to me are The Tree of Architecture by Banister Fletcher and The Evolutionary Tree by Charles Jencks, that try to capture your essence and, in the process, unashamedly leave out the global south (19 sends Arch images of the diagrams).

Africa doesn’t appear as a root, a branch, a leaf, a fruit; nothing, as if it could be simply and conveniently pruned off. The use of a tree as a metaphor is apt, and those diagrams demonstrate how not only is Eurocentric ideology at the root of your foundations, it is also all that you can produce. It’s in fact those values that give you the permission to co-opt outsider and peripheral participation, such as yourself, as progress. You are able to absorb or take on the physical characteristics of a historical ‘Other’ through their socio-economic assimilation. Stuart Hall describes that form of representational change as an act of reconstruction rather than reflection, and says that the one in control of it is producing fictions that dictate, and in your case, cement belief and perception. It’s such a powerful practice; you’re essentially producing momentary ‘facts’ i.e., myths.

Arch: I struggle to simply accept that, because that would mean that the way we are the discipline or participate in it must be negligible, and I just can’t believe that to be true! I also don’t just want to replace that Eurocentric value system with my own, as if mine is intrinsically flawless and faultless. I don’t want to lean into righteous rage or revenge. How do you choose what to tear down and what to keep? Surely you can afford one grace for not knowing, no?

19: Definitely. We are however able to start with some of the more obvious conditions like (19 sends Arch an image) apartheid spatial planning7, which I guess is where you’ve been starting, but I’m proposing that we start at the level of myth-making, where we begin to investigate what the unjust and mostly inherited values are that we are upholding and ritualizing; and to begin to design and institutionalize the values we prefer for ourselves. Sometimes just a small practice of values can go a long way in giving oneself the permission to live by them wholly. Last year for instance, I produced my own prizegiving, on top of our school prizegiving, as a way of articulating and rewarding what I value, such as risk over pristine outcomes, community support over competitive individual achievement and so on. I believe that those small practices must ultimately spill into how I approach everything, including the practice of my craft. You never showed me how to build value systems Arch, you only showed me how to sustain existing ones. I’d like to opt out of that and be at the forefront of my own forms of creation.

Arch: Well 19, with the amount of lives that I’ve lived and the number of times that I have been challenged, nit-picked, stretched and strained, I’ve come to learn that my response to your decisions won’t matter; it shouldn’t matter. You know I can’t really stop you or the direction you choose, just as much as you are maybe realizing that you can’t stop me either. So, to your point of things being able to coexist without posing a threat to one another, you

might have to concede to the idea of seeing me in more nuanced ways than just corroded.

19 remains in quiet contemplation on the line.

Arch: 19?

19: Yes, I’m still here. I’m just processing what you’ve said.

Arch: (as if gloating) Well while you do that, I’m going to say goodbye and keep working on my very flawed project in front of me that has a budget, client, deadlines and overall buy-in, hehe.

19: Please, that doesn’t mean anything to me. It just shows –

Arch: Oh 19, relax! You’ll also have to learn how not to take yourself so seriously. You sure can dish it but not quite take it. Anyway, until the next time.

19: (embarrassingly) Next time? There shouldn’t be –

Arch hangs up on 19. He stares at his phone and 19 lets out a contemplative laugh.

19: Okay Arch, okay.

NOTES:

1 One of South Africa’s most successful inner-city regeneration projects of areas declared no-go zones as a result of urban decay and crime. Maboneng, which is a Sotho word meaning “place of light”, is a creative hub frequented by urban artists, and comprises of restaurants, coffee shops, clothing boutiques, art galleries, and retail and studio space. Projects such as this represent tensions around ideas of gentrification (Maboneng Precinct [sa]).

2 White flight or white exodus is the sudden or gradual large-scale migration of white people from areas becoming more racially or ethnoculturally diverse (White Flight 2021).

3 Rivonia is one of the most historically and current affluent suburbs in Johannesburg. It is most famous for Lilieslief Farm, which was used as a safe house for African National Congress (ANC) activists in the 1960s. In 1963, the South African police raided the farm, arresting more than a dozen ANC leaders and activists, including Nelson Mandela. Characteristic to the domestic spatial typologies such historically white areas have servant’s quarters are at the back of the yard (Liliesleaf Farm 2021).

4 The houses built in new Black ‘locations’ by the newly incumbent Apartheid regime after 1948 in South Africa were as a result of research conducted by the National Building Research Institute (NBRI) between 1948 and 1951. While a group effort, much of that implemented resulted from the ideas of Douglas Calderwood, a young architect working at the NBRI at the time. He subsequently incorporated his work into two academic studies for which he was awarded an MArch and, later, a PhD, by the University of the Witwatersrand School of Architecture. The dwellings were the design of another young architect employed by the NBRI, Barrie Biermann, now remembered for his research in Cape Dutch architecture. Biermann›s knowledge of the Cape Vernacular is evidenced by the plan of the standard house. It became generally known as the NE 51/6, where ‹NE› stood for Non-European, ‹51› was 1951, the year of Calderwood›s doctoral thesis, and ‹6› was the drawing›s number in the thesis. Other designs included the NE 51/7, consisting of a pair of semi-detached NE 51/6s, and the NE 51/9, a slightly larger version of the NE 51/6 with an internal bathroom (NE 51/1-9 [sa]).

5 The Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) is intended as an integrated, coherent socio-economic policy framework. It seeks to mobilize all South African resources toward the final eradication of apartheid and the building of a democratic, non-racial and non-sexist future (The Reconstruction and Development Programme 1994).

6 University of the Witwatersrand.

7 Apartheid is a system of institutionalized racial segregation that was lawfully instituted in South Africa between 1948 and 1994. It was a system used by the minority white Afrikaans population to effectively oppress, control, and rule over the majority native Black South Africans. Apartheid architecture (also called Apartheid spatial planning) segregated communities into territories along racial lines, ensuring that black community labour camps (known as townships) were devoid of economic and gathering opportunities (they believed that if black populations were given the chance to gather and possibly organize, that would have serious political implications). The used what they called the 40-40 rule, where they designed the townships to have 40sqm sized homes, placed 40km away from white-designated towns with job opportunities to force black South Africans to spend 40% of their income commuting; this limiting what income they had left over to develop their homes and communities (Baldwin 2020).

REFERENCES:

1. Baldwin, E. 2020. ‘“I Grew Up Where Architecture Was Designed to Oppress”: Wandile Mthiyane on Social Impact and Learning from South Africa’. [O]. Available: <https://www.archdaily.com/947507/i-grew-up-where-architecture-was-designed-to-oppress-wandile-mthiyane-on-social-impact-and-learning-from-south-africa> [Accessed 20 January 2021].

2. Hall, S. ‘Decoding cultural oppression’. [O]. Available <http://.corwin.com/sites/default/files/upm-binaries/13286_Chapter_2_Web_Byte__Stuart_Hall.pdf> [Accessed 22 February 2017].

3. Liliesleaf Farm. 2021. [O]. Available: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liliesleaf_Farm> [Accessed 10 January 2021].

4. Liphosa, P. & Dennis, N.O., 2017. ‘Solomon Mahlangu House: self-assertion and humanisation through claiming black space’. [O]. Available: <https://www.cairn.info/revue-clara-2017-1-page-49.htm> [Accessed 18 January 2021].

5. Local Studio WITS Gateways. [Sa]. [O]. Available: <http://localstudio.co.za/arch-project-post/wits-gateways/> [Accessed 20 January 2021].

6. Macharia, K. 2018. ‘black (beyond negation)’. [O]. Available: <https://thenewinquiry.com/blog/black-beyond-negation/> [Accessed 21 January 2021].

7. Maboneng Precinct. [Sa]. [O]. Available: <https://gauteng.net/attractions/maboneng_precinct/#:~:text=Maboneng%2C%20a%20Sotho%20word%20meaning,energy%20for%20Johannesburg’s%20urban%20artists> [Accessed 15 January 2020].

8. McKittrick, K. ed., 2015. Sylvia Wynter: On being human as praxis. Duke University Press.

9. Ne51/1-9. [Sa]. [O]. Available: <https://www.artefacts.co.za/main/Buildings/style_det.php?styleid=1556> [Accessed 15 January 2021].

10. Philosophize this! Podcast by Stephen West. Episode 116. [O]. Available: <https://open.spotify.com/episode/2n2nVuPQGO2Mp87bR8W6g0X2?si=MzJ7kxx_SHKrkztsvGvWZg> [Accessed 13 January 2021].

11. The Reconstruction and Development Programme. 1994. [O]. Available: <https://omalley.nelsonmandela.org/omalley/index.php/site/q/03lv02039/04lv02103/05lv02120/06lv02126.htm> [Accessed 15 January 2021].

12. Seekings, J. and Nattrass, N., 2008. Class, race, and inequality in South Africa. Yale University Press.

13. Van Niekerk, G. 2017. ‘South African Architecture Is Failing To Transform’. [O]. Available: <https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/2017/11/07/south-african-architecture-is-failing-to-transform_a_23268987/guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAKDyrvVgf8NlltrjcDR_ym_d_8Gk7bYvqYzKTf6SkJUoF8iXsNwrngd6E4f785UuYeMoRZJLo4b4ctsr0joI8WjPuIyZa7Dpx9YfOuZCVc2uFg21TpU5tPetSr3gsGKqZSRyibccgls43HquUH4pZJ6nUjFLnM43rkGZ72JXu> [Accessed 20 January 2021].

14. White Flight. 2021. [O]. Available:<https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/White_flight#:~:text=The%20term%20’white%20flight’%20has,and%20anti%2Dcolonial%20state%20policies> [Accessed 10 January 2021].

Additional readings:

Hill, J. 2016. ‘Alejandro Aravena and the Future of the Pritzker Prize’. [O]. Available: <https://www.world-architects.com/en/architecture-news/insight/alejandro-aravena-and-the-future-of-the-pritzker-prize> [Accessed 25 January 2021].

Mbuyi, T & Schinagl, M. 2014. ‘Decoding Operation Clean Sweep: The Place of Street Traders in the ‘World Class African City’’. [O]. Available: <https://informalcity.wordpress.com/2014/05/21/decoding-operation-clean-sweep-the-place-of-street-traders-in-the-world-class-african-city/> [Accessed 20 January 2021].

Strijdom Square plans were never approved. 2001. [Sa]. [O]. Available: <https://www.engineeringnews.co.za/article/strijdom-square-plans-were-never-approved-2001-08-24/rep_id:4136> [Accessed 21 January 2021].

Symbols trailing tyrannies of the past. 2013. [Sa]. [O]. Available: <https://mg.co.za/article/2013-05-10-symbols-trailing-tyrannies-of-the-past/> [Accessed 20 January 2021].

Comments